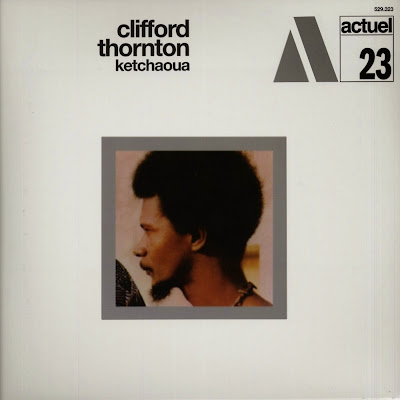

Label: Delmark Records – DS-415

Format: Vinyl, LP, Album / Country: US / Released: 1968

Style: Free Jazz, Free Improvisation

Recorded at Sound Studios: Track A1 on March 27, 1968; Tracks B1 & B2 on April 10, 1968.

Cover, Artwork – Zbigniew Jastrzebski

Liner Notes – John Litweiler

Photography By [Cover] – Ray Flerlage

Producer [Album Production And Supervision] – Robert G. Koester

Recorded By – Ron Pickup

A - 840M (Realize) ................................................ 19:50

(Composed By – Anthony Braxton)

B1 - N-M488-44M-Z ............................................... 12:50

(Composed By – Anthony Braxton)

B2 - The Bell ........................................................... 10:20

(Composed By – Leo Smith)

Anthony Braxton– alto, soprano saxophone, clarinet, flute, bagpipes [musette], accordion,

bells, drums [snare], mixed

Muhal Richard Abrams– piano, cello, alto clarinet

Leo Smith– trumpet, mellophone, xylophone, percussion [bottles], kazoo

Leroy Jenkins– violin, viola, harmonica, bass drum, recorder, cymbal, whistle [slide]

Anthony Braxton’s debut LP introduced an unconventional, often controversial new talent whose career – spanning decades and still going, without nearly enough attention, today – has been one of the most fascinating in jazz. At the time this was recorded, Braxton was just under 23 years old, an affiliate of the Chicago-based Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), which had been active (but barely documented on record) since 1965. The boldly titled 3 Compositions of New Jazz was among the first statements of the group, preceded by AACM co-founder Muhal Richard Abrams’ Levels and Degrees of Light (on which Braxton made his first recorded appearance; his own debut was his second) and some of the albums that would lead to the formation of the Art Ensemble of Chicago, with records by Roscoe Mitchell and Joseph Jarman featuring the extended AACM family.

3 Compositions resonated with the aesthetic being forged on these late ’60s albums. This was a radical new sound in free jazz, paring back the unrelenting energy and frenzied blowing sessions that had become de rigueur in favor of space, extreme dynamics, humor, and versatility in both instrumentation and style. Ironically, given the chilly reception with which this scene was greeted at the time, Braxton’s late ’60s/early ’70s work made in the orbit of the AACM was one of the last times in his career that the iconoclast composer would actually fit comfortably into any larger tradition or collective.

The AACM formed a solid foundation for Braxton’s early musical experiments. He joined the group in 1966, immediately after returning from a stint with the Army Band, stationed in South Korea. At this point, the AACM was very active in Chicago, with a huge membership whose activities frequently overlapped and intersected. Braxton played with many of his AACM peers during this time, putting in his apprenticeship in the groups of Abrams, Jarman, Mitchell, Gerald Donovan, and others. These groups weren’t recorded and didn’t make much impact outside their hometown at the time, but the wildly creative atmosphere encouraged Braxton to push himself; he was both directly influenced by many of these musicians and inspired by them to come up with his own unique contributions.

The AACM’s influence started to expand beyond Chicago towards the end of the ’60s, as some documentation of these musicians finally trickled out. From 1968-1970, Braxton recorded a string of albums with likeminded musicians from the AACM. In particular, he formed a regular trio with violinist Leroy Jenkins (who like Braxton had debuted on Levels and Degrees) and trumpeter Leo Smith, sometimes adding Abrams (as on the B-side of 3 Compositions) or drummer Steve McCall. Once this group moved to Paris in mid-1969, they were known, for a short time, as the Creative Construction Company, but while the Art Ensemble (who also went abroad) flourished in that milieu, the CCC quickly broke up and Braxton briefly gave up on music, moving to New York to play chess.

Regardless, this was a vital and productive era for all these musicians, who were rapidly developing new musical ideas and expanding the possibilities of jazz, at times making music that pushed beyond even the most liberally defined boundaries of the genre. Such concerns would be a hallmark of Braxton’s career, and this album proves both a valuable document of early AACM ideas and a first hint of Braxton’s own idiosyncratic aesthetic.

The Braxton/Jenkins/Smith trio was characterized, like many of the AACM musicians, by their multi-instrumentalism, and none of them stick to any one instrument for very long, particularly on this album’s side-long first piece. Among other variations, Braxton and Jenkins insert primitive drumming, Jenkins plays harmonica, Smith plays bottles, and Braxton plays accordion and bells in addition to his saxophones and clarinet. This kind of instrument-switching and insertion of unusual sound-making devices was a key innovation of the early AACM. It enriches and complicates the texture of the music, introducing novel and even lowly sounds, challenging the idea of jazz virtuosity with a palette that’s as open to junk and clatter as it is to speed-blurred sax solos. This trio was also, like the early Art Ensemble before Don Moye joined, unmoored from rhythm by the absence of a regular drummer: all the musicians contribute percussion, but there’s no one keeping time or providing a steady percussive backdrop of any kind, so the music floats freely and time seems to stretch while they’re playing.

The A-side of 3 Compositions is a 20-minute piece written by Braxton, titled, like most of his compositions, with a combination of graphic symbols and abbreviations, though it’s easiest to refer to his work using the retroactively applied opus numbers; this is “Composition No. 6E.” The LP opens with what might be thought of as the “head” of the tune, except that it’s carried by the musicians harmonizing “tra-la-la” and gradually adding instruments like slide whistle and kazoo. The playful instrumentation on “6E” suggests this group’s determination to toy with tradition. This piece, especially, was a remarkably risky way for the young trio to introduce themselves. The music is spiky but languid, spacious but not without momentary bursts of aggression. It’s meandering music that gradually wanders its way into being.

The composition is a “vocal piece for trio,” a likely callback to Braxton’s youthful love of doo-wop. That interest in non-jazz forms of black music was another point of correspondence between Braxton and the rest of the AACM musicians, one that’s not often attributed to him. He’d subsequently come to be seen as quite distinct from the rest of the AACM, and the Art Ensemble would be the group most known for gleefully mixing R&B with jazz, but even from this early stage an awareness of, and affection for, a broad spectrum of black music has always been one current in Braxton’s music as well. (Braxton even toured with the soul duo Sam & Dave in the mid-’60s, though they quickly fired him for playing too free.)

The vocals mostly appear at the beginning and end of “6E,” as the group sings the theme in rough harmony, then echoes the melody on a slide whistle with jangling bells in the background. From there, the simple melody provides a jumping-off point for further elaborations and improvisations. The basic structure isn’t too dissimilar from the head-solos-head format of much earlier jazz, but the thematic material, and the way the group approaches it, deviates substantially from what’s expected in the form.

It takes almost two minutes for Braxton to enter on sax, high and sweet, stating the melodic figure more conventionally – and even then, his rich, full line is assaulted from every side by Jenkins’ parodically simple harmonica, clanking percussion, and continued out-of-tune mumbling/singing. After another couple of minutes of this, Smith finally picks up his trumpet and Jenkins switches to violin, meaning that it takes four minutes for all three players to actually play their primary instruments.![]()

![]()

Braxton, of course, drops out almost immediately to play a crude martial drum beat. The music is constantly shifting in this manner, with new combinations and textures being introduced at every moment. There’s a sense of delightful, mischievous amateurishness to a lot of the proceedings; all three men are masters of their main instruments, but they’re constantly throwing so much else into the mix that it makes the very idea of instrumental technique seem like a distant secondary concern at best. The music is balanced between the strange beauty of its often submerged thematic material, the eerie, haunting quality of many passages, and the charming humor with which the musicians undercut and subvert those more serious, emotional currents.

There’s a particularly sublime passage almost halfway through where Braxton, Smith and Jenkins actually do converge as a sax/trumpet/violin trio. Smith’s guttural trumpet interjections prompt Braxton to push his own line from melodic improvisations into squealing upper-register explorations, and Jenkins joins with screechy violin patterns serving as a makeshift rhythm section. The thick, dense sound becomes difficult to probe, with the trio seamlessly melding their individual sounds into a single grand clamor.

When, after all this woolly, wandering improvisation, the “head” finally returns in recognizable form at the very end of the piece, it beautifully completes the joke. The piece is both a parody of traditional jazz structure and an affirmation of the form’s possibilities. “6E” at least kind of sticks to the rules – its theme statements bracket group improvisation – but it does so much within those loose boundaries that would never be expected or tolerated in even the most “out” jazz performances of the time.

Abrams joined the trio for the record’s B-side, which is split between another Braxton composition (“6D”) and Smith’s “The Bell.” Abrams plays piano on “6D,” laying down a steady, almost unceasing bed of frenzied chords, occasionally sweeping scales up the keyboard and generally filling every available space. In Braxton’s terms, the piece is concerned with “fast pulse relationships,” an apt summation of Abrams’ percussive playing here. One of the only rests comes, with a sly wink, after the chaotic 10-second fanfare that opens the piece: a few seconds of dead silence, and then it’s back to the maelstrom. Because of this constant foundation, this track winds up being far less radical than “6E.” It’s a more conventionally structured piece, especially by the standards of late ’60s free jazz: after the initial chaos with everyone playing at once, the musicians politely take turns soloing atop Abrams’ pounding base, sticking to their primary instruments and laying out when another soloist is playing. This is not a structure that would appear often in Braxton’s ouevre. Much of the challenge and originality of his ensemble work is rooted in his quest for new structures and new composition/improvisation and composer/performer balances within his music.

Even with only Abrams and one other musician playing at any given time, the group makes an impressive racket. Smith is up first with a concise, confident trumpet line, varying the dynamics between bold, clean notes and passages that have a muffled quality, as though played from a distance. These shifts actually work quite well with Abrams’ piano: the trumpet vacillates between speaking clearly over the background or shyly letting its statements disappear into the accompaniment. Jenkins’ violin solo, by contrast, is lengthy and meandering, quickly running out of ideas as he scrapes the strings in a manner that coheres all too well with Abrams’ relentless virtuosity.

Unsurprisingly, Braxton’s alto sax solo is lively and vibrant, flexibly shifting from rapid streams of notes to harsh squeals and little playful asides before heading imperceptibly back to the main line. Inspired by Abrams and AACM horn players like Mitchell and Jarman, Braxton was starting to perform solo alto sax concerts around this time, and within a year he’d record his landmark For Alto, a double LP of solo saxophone music. Already it’s obvious that he’s something special as a soloist, but Abrams doesn’t give him much room to play with the pacing or dynamics. When Braxton pauses for effect, the space is merely filled in with relentlessly hammering piano. Abrams’ own solo spot, at the end of the piece, before another burst of chaotic group playing, varies a bit from the carpet of sound, introducing some loping rhythms and dynamic shifts, but the overall effect is still monotonous. If “6E” represented this band satirizing and playfully expanding the parameters of late ’60s free jazz, “6D” finds them cohering to the status quo, a rarity in Braxton’s work.

The final piece on the album is the Smith-penned “The Bell,” which returns to the restraint and dynamics of the A-side, albeit without quite the same raucous sense of humor. This is, rather, a stately and relaxed piece that documents Smith – a great and sadly undervalued composer and musician – at an early stage of his evolution, much as the rest of the album does for Braxton.

The first half of the piece is dominated by Jenkins’ violin, played gently and softly, emitting long, mournful tones that quiver and fade. The other musicians similarly play in ways designed to let tones decay and waver towards silence. Braxton inserts breathy, rustling sax interjections, Smith plays slow, interrupted lines with plenty of space and pauses, and Abrams switches between piano, cello, and clarinet but contributes only momentary shadings no matter which instrument he’s on. The overall mood of the music is hushed and expectant. In the second half, the sound becomes even more sparse and pointillist, with occasional jarring horn blurts intentionally adding an uneasy quality, shattering the peace. A metronome ticks away relentlessly in the background, setting the steady time that would usually be supplied by a conventional rhythm section; here, the group seemingly ignores even that rudimentary rhythm, setting their own patient pace.

Despite its quietness and seeming simplicity, this is intense, involving music, torn between serenity and tension, playing with space and silence in ways that anticipate Smith’s subsequent ’70s recordings, both solo and as leader of the shifting-membership ensemble New Dalta Ahkri. It’s much less indicative of the directions in which Braxton himself would head after his initial forays under the AACM aegis. As a result, the inclusion of this piece here adds to the album’s eclecticism and contributes to the sense that it’s a true document of a few different currents within the varied early AACM, not just a snapshot of the young Braxton’s interests.

Indeed, the AACM is so fascinating precisely because it represented the intersection of so many strong, individualist visions, so many musicians pursuing their own ideas in many different ways, united mainly by a commitment to following their own idiosyncratic visions, rather than by the specifics of the visions. 3 Compositions is notable for introducing Braxton, one of jazz’s most singular composers and musicians, but with the input of Smith, Jenkins, and Abrams (the latter a crucial mentor to all these musicians and many more) it’s also a valuable cross-section of the AACM during its unruly, inventive, under-documented first phase, before the collective, with all its disparate intellects and ideas, became virtually synonymous with the Art Ensemble of Chicago.

50 Years of AACM - Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians

If you find it, buy this album!

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)