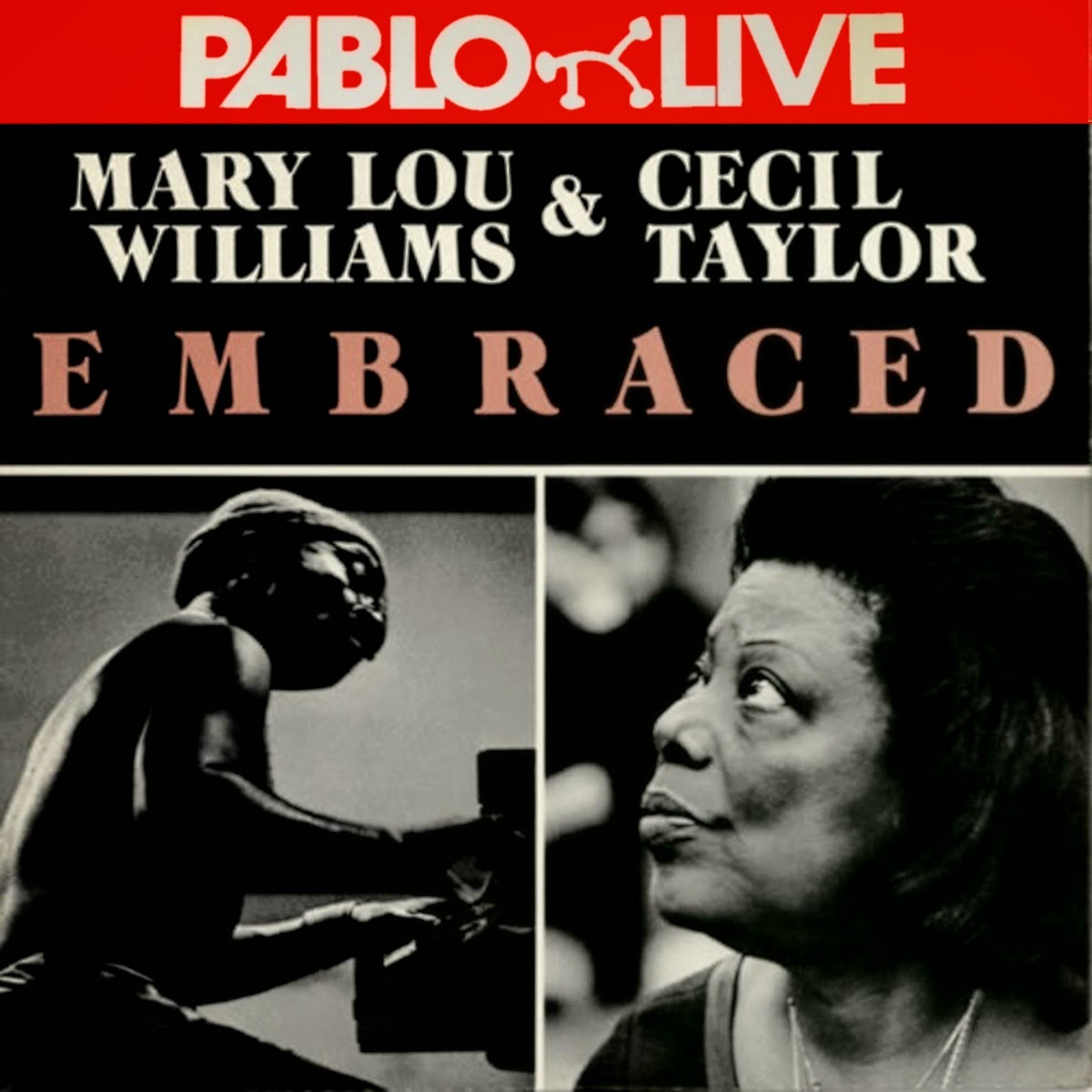

Label: Pablo Live – 2620 108

Format: 2 × Vinyl, LP, Album / Country: US / Released: 1978

Style: Contemporary Jazz, Free Improvisation

Recorded live on 17 April 1977 at Carnegie Hall in New York City.

Design [Cover] – Norman Granz, Sheldon Marks

Photography By – Phil Stern

Producer – Cecil Taylor, Mary Lou Williams

Phonographic Copyright (p) – Pablo Records

A1 - The Lord Is Heavy (A Spiritual) . . . . . . . . . . 6:09

A2 - Fandangle (Ragtime) . . . . . . . . . . . 1:15

A3 - The Blues Never Left Me . . . . . . . . . . 5:00

A4 - K.C. 12th Street (Kansas City Swing) . . . . . . . . . . 12:32

B1 - Good Ole Boogie . . . . . . . . . . 5:35

B2 - Basic Chords (Bop Changes On The Blues) . . . . . . . . . . 7:40

C1 - Ayizan . . . . . . . . . . 14:22

C2 - Chorus Sud . . . . . . . . . . 9:25

D2 - Back To The Blues . . . . . . . . . . 14:47

D3 - I Can't Get Started . . . . . . . . . . 4:10

Mary Lou Williams – piano

Cecil Taylor – piano

Bob Cranshaw – bass

Mickey Roker – drums, percussion

A masterful meeting of two important of piano genius – Mary Lou Williams and Cecil Taylor – sounding incredibly here in each other's company! The set features a core rhythmic pulse from Mickey Roker on drums and Bob Cranshaw on bass – and Williams and Taylor really take off on their twin pianos – with Cecil almost leading Mary Lou more into territory of his own, although she also brings an undercurrent of soul to the set that makes the record unlike any other that Taylor ever recorded! The approach shouldn't work, but it's captivatingly brilliant from the start – as you'll hear on tracks that include "The Lord Is Heavy", "Good Ole Boogie", "Basic Chords", "Ayizan", "KC 12th Street", "Fandangle", and "Chorus Sud". _ © 1996-2015, Dusty Groove, Inc.

When pianist Mary Lou Williams decided she wanted to perform with legendary iconoclast Cecil Taylor, she figured it would be a love fest. But as the concert and resulting album Embraced attest, it was anything but amore. This excerpt from Linda Dahl’s book, Morning Glory: A Biography of Mary Lou Williams (Pantheon Books), tells the story.

Many people wondered why Mary chose to perform in a dual-piano concert at Carnegie Hall with Cecil Taylor, perhaps the ultimate avant garde pianist. She had repeatedly made her negative feelings clear about the avant garde in jazz, with its rejection of established harmonic and tonal patterns. In an essay that became part of her liner notes for Embraced, the album resulting from her concert with Taylor, she described the avant garde as being filled with “hate, bitterness, hysteria, black magic, confusion, discontent, empty studies, musical exercises by various European composers, sounds of the earth, no ears, not even relative pitch and Afro galore (although”—she hastened to add—”I’m crazy about African styles in dress”).

Yet something in Taylor’s music appealed to her, as did John Coltrane’s late playing; or, rather, she accepted both musicians’ work because they could still, if they wanted to, play “within the tradition.” And although tradition—the heritage of suffering embodied in spirituals and the blues—was sacred to her, Mary had always pushed herself to experiment and master new styles of black music. And by the mid-’70s, she was eager to reposition herself on the cutting edge. She was not, she wrote in her diary, “corny” (her word for passé and hidebound); no, she had “changed with the times.” Still, by then she had felt at least a twinge at being passed over. So much had happened since her reemergence in the ’60s—rock, soul, long hair, Afros.

It was, then, in the spirit of reconciliation between the two “camps” of jazz (avant garde versus everything that came before) that Mary conceived the idea of doing a concert with that lion of “out” players, Cecil Taylor. He had won her over with his admiration for her playing. Actually, he’d been listening and appreciating Mary’s music for a long time, since 1951, when he first caught her at the Savoy Club in Boston while a conservatory student in that city. “She was playing like Erroll Garner, but her music had a lot of range,” Taylor said in a rare interview. Almost two decades passed before Mary, in turn, listened to Taylor—during his engagement at Ronnie Scott’s in 1969. Then, in 1975, Taylor really began listening to Mary, dropping by the Cookery often. And each time he came into the club, as Mary remembered it, he’d move closer to the piano, until, she said, “He sat down one night at the end of the gig and played, but a little too long,” clearing out the club. But when Taylor told her, “No one’s playing anything but you,” Mary’s reaction was, at first, “Here’s somebody else putting me on.” But he kept showing up to listen, and eventually Mary broached the idea of doing a concert together. (It was Taylor who came up with the title, Embraced. In response, Mary drew a picture of three concentric circles, symbolizing, as she saw it, her music, his and the music of their interplay.)

Organizing the April 17, 1977, event fell to Mary, who followed her usual game plan. Friends received photocopied requests: “Help save this precious music and keep me out of Bellevue! Smile! Send checks for your tickets or donations.” Despite such efforts, made at her own expense, and Peter O’Brien’s publicity, the house at Carnegie Hall was no more than half-filled and Mary just broke even on the concert.

But it would be a hall filled with partisans of the two pianists, and speculation ran high about what sort of jazz would emerge from the meeting of two such strong musicians—for if Taylor was a lion at the piano, Mary was a lioness. To Village Voice jazz writer Gary Giddins, the concert promised to be “doubly innovative for bringing together two great keyboard artists in a program of duets, and for dramatizing the enduring values in the jazz-piano tradition.” But hints of a possible musical fiasco were also in the air. Rehearsals revealed frayed nerves and disparate purposes. Cecil Taylor had never shown any desire to play predetermined music from a written score, although Mary claimed that for the first half of the concert he’d agreed to play the new dual-piano arrangements of spirituals she’d written, using her “history of jazz” approach. Then, after the intermission, they would use “rhythm patterns as a shell,” in Mary’s words. “When Cecil is doing his things, I’ll start moving in his direction. I’ll play free and then I’ll jump back to swinging.” But in the hours before the concert began Taylor fumed. Not only had she written a part for him—a “free” player of the first rank—but she had not consulted him about the rhythm section—her own—that was to accompany them for the first half. To Mary, of course, this seemed fair: she got the first half, and he got the second half of the concert. But as Taylor told a journalist, Mary “wanted him to play her music but [she] refused to perform his music the way he wanted it heard. We are not certain exactly how the concert will be structured,” Taylor warned.

Clashed would be a more accurate title than Embraced for the music that ensued; the concert confirmed gloomier predictions. Reviewers tended to write about it more as a contest than a collaboration: “The result was at best a tug of war in which Mr. Taylor managed to remain dominant,” wrote the New York Times. On “Back to the Blues,” to take one example, Taylor plunges deep into his favorite nether musical regions. It takes Mary’s strongest playing, the signature crash and crush of her left hand at full throttle, to tug the piece back from outer space. When, as Gary Giddins described Taylor, “the predatory avant gardist” overreached Mary’s “spare, bluesy ministrations,” she called in the rhythm section quite as if she were calling in the troops.

Listeners—at least those in Mary’s camp—saw little of the “love” she had urged Taylor to play after the difficult first half. Backstage, fur flew. “I slammed the door on him hard,” says Peter O’Brien, “and saxophonist Paul Jeffrey, who was listening backstage, had to be physically restrained from punching him. Mary came off the stage and said to me, ‘Oh man, I played my ass off.’ And she did, but I made her go back out there.” Her adrenaline was up and Mary played brilliant encores—”Night in Tunisia,” “Bag’s Groove,” and “I Can’t Get Started,” the last a frequent source of inspiration for Mary.

Perhaps the best review, though never published, came from Nica de Koenigswarter, in a letter she shot off to Mary after the concert, written in the jazz baroness’s beautiful hand and careful multicolored underlinings:

Rather than an ‘embrace,’ it seemed to one like a confrontation between heaven and hell, with you (heaven) emerging gloriously triumphant!!! I know it wasn’t meant to be that way, but this is the way it seemed. I also know what a sweet cat C.T. is and what beautiful things he writes, in words, that is, but the funny part is that he looks just like the Devil when he plays as well as sounding like it, as far as I am concerned, sheets of nothingness, apparently seductive to some. Anyway I loved Mickey Roker and Bob Cranshaw for seeming like guardian angels, coming to your defense and it was worth it all to hear you bring it back to music.

Love you, Nica

Two years later, Mary could joke a little about the concert. “When I was coming along, it wasn’t enough just to play. You had to have some tricks—I used to play with a sheet over the piano keys. So when Cecil started playing like that and kept on going, I started to get up from the stool, turn around and hit the piano with my butt—chung, choonk! That woulda got them!” She revealed her hurt only to her fellow artist in a letter two years after the fiasco:

Cecil! Please listen if you can. Why did you come to me so often when I was at the Cookery? Why did you consent to do a concert? You felt I was a sincere friend. In the battlefield, the enemy (Satan) does not want artists to create or be together as friends.

Cecil, the spirituals were the most important factor of the concert (strength), to achieve success playing from the heart, inspiring new concepts for the second half. I wrote you concerning the first half. You will have a chance to listen to the original tapes and will agree that being angry you created monotony, corruption, and noise. Please forgive me for saying so. Why destroy your great talent clowning, etc.? Applause is false. I do not believe in compliments or glory, my inspiration comes from sincere love. I was not seeking glory for myself when I asked you to do the concert. I am hoping you will reimburse me for 30 tickets—would you like to see the receipts?

I still love you, Mary

Within six months of her concert with Taylor, Mary was back at Carnegie Hall for another concert with another difficult musician, as a “special guest” in January of 1978 in a 40-year “reunion” concert at Carnegie Hall. Billed as “An Evening with Benny Goodman,” the concert attempted to recreate the spirit of the famous 1938 concert where Goodman had been dubbed “King of Swing.” But the 1978 event was a disappointment, underrehearsed, ragged, with Goodman off balance. Mary played gamely and took a sparkling solo on “Lady Be Good,” but the gig was just a gig to her, a way to pay bills. (When Goodman approached her afterwards about doing a record together of Fats Waller tunes, she declined.)

After going from playing with way-out Cecil Taylor to comping for Benny Goodman—a breathtaking musical leap few pianists would attempt—Mary could declare with satisfaction, “Now I can really say I played all of it.”

Playing “with” Cecil: The Rhythm Section Reflects

On Embraced, the album that documents the meetingbetween Mary Lou Williams and Cecil Taylor, the former closes the concert with a solo version of “I Can’t Get Started.” The way the concert’sbassist, Bob Cranshaw, tells it,Taylor’s performance should be titled “You Just Can’t Stop Me.”

“Cecil was gone. There was nothing going to stop him from playing once he got started,” Cranshaw remembers. “Cecil went on a piano back stage and just kept playing during the intermission!”

Williams got angry, according to Cranshaw, because he and drummer Mickey Roker, not knowing what to do, just kept playing along with Taylor when she wanted the concert to stop. Williams thought they were egging Taylor on.

“He stormed over both of us. She was pissed and we were dying laughing because we didn’t know what to do,” he recalls. “Mickey said, ‘Look, what do you want us to do? Grab him by the arms and carry him off stage?’” Cranshaw laughs.

But Roker willfully remembers little of the event. “I tried to do all I could to forget that [concert]! It was confusing. And music shouldn’t be confusing. Music should be festive,” he says. “The record speaks for itself. I don’t enjoy that kinda thing.”

Cranshaw admits he never heard the recording and he, too, says it was all very confounding. “I wasn’t sure if I wanted to hear it,” he says. “I never thought I played well on it to begin with.”

— By Christopher Porter (JazzTimes)

Well, what a tense story ... Listen to the album and... judge for yourself.

Enjoy!

Well, what a tense story ... Listen to the album and... judge for yourself.

Enjoy!

If you find it, buy this album!